A Violinist’s Blog

Biber's Passacaglia and its mysteries

THE MYSTERIES WITHIN BIBER’S PASSAGALIA

Background

Biber (1644-1704) ends his great cycle of 15 ‘Mystery’ Sonatas for violin and continuo, perhaps rather strangely, with a 16th final piece for unaccompanied violin, the famous Passacaglia (or Passagalia as it is spelled in the surviving manuscript). Some commentators seem to regard it as an afterthought, tacked on at the end without truly belonging to the sonatas. Most point out that, at its head, it has an engraving of the Guardian Angel leading a child by the hand, which may suggest performance at the Feast of the Guardian Angel on 2nd October, some claim that the four falling notes on which it is based, though a common ground-bass of the period, are also the first four notes of a contemporary German hymn, ‘Einen Engel Gott mir geben’, but there most comment seems to dry up. This article aims to uncover some of its message and open up some of its symbolism.

The date of composition of the whole cycle is somewhere between 1670 and 1680, after Biber’s appointment as director of music to the Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg, Maximilian Gandolph. ‘I have consecrated the whole to the honour of the XV Sacred Mysteries which you promote so strongly’, says Biber in his dedication of these works to him. The Mysteries are those of the Rosary and each of the cycle of fifteen sonatas is inspired by one of the mysteries and is prefaced by an engraving, probably cut from a Rosary psalter. The Aula Academica of Salzburg’s University, which still contains fifteen paintings depicting the mysteries, may well have been the place where these works were performed and they were probably written for the Rosary devotions there, in September and October, which were associated with the Feast of the Guardian Angel.

Both Biber and the Archbishop were Jesuits, probably the most important and influential of all the religious orders active in central Europe at this time, and for them devotion to the Rosary was central. The Jesuits were founded in the sixteenth century by the Spaniard, Ignatius of Loyola, later to become St Ignatius, after whom Biber adopted one of his middle names, Ignaz.

Structure

At its most simple, the Passagalia consists of 65 statements of the ground bass divided into 30 + 15 + 20 (in the proportion 6:3:4), where the central section is marked by the ground bass rising an octave, but this in itself says very little about the piece musically.

It could also be analysed according using the ‘Golden Section’, the piece dividing at the first adagio into the rather satisfying ratio of 48:84 (4:7). These main sections divide too, into 18 + 30 (3:5) and 52 + 32 (13:8). These last two ratios come from the Fibonacci series (1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, etc.) while the first comes from the related ‘Lucas’ series (1, 3, 4, 7, 11, 18 etc.). Pairs of numbers in these and other similar series get closer and closer towards the ‘Golden’ ratio (approximately 0.618 : 1) as the series progress. (In simple terms, a line divides at the Golden Section when the smaller part to the larger part are in the same ratio as the larger part to the whole.)

However, both these schemes seem to militate against the very clear divisions created by the reappearance of the ground bass unadorned. This clear punctuation creates unequal sections and signals distinct mood changes. For well over 30 years I have felt that these changes of mood must represent something, some spiritual message or symbolism. The piece also clearly divides exactly in half (66 + 66 bars – there is a very clearly notated silent bar at the end, and at bar 67 the highest note of the piece is reached). That 66 is a multiple of 33, the traditional number of years of Christ’s life, persuaded me to delve deeper.

The Guardian Angel and the Child

The Jesuits in the 17th century seem to have been largely responsible for popularising devotion to a guardian angel. And the appearance of the child cannot help but remind us of Jesus’ words in St Matthew’s gospel, ‘Truly I tell you, unless you change and become like children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.’ St. Ignatius himself used direct simple language, sometimes clearly intended for children, when explaining theological points. Perhaps Biber was combining two important religious preoccupations of the time. My first thoughts about the engraving of an Angel leading a child by the hand were that perhaps the piece is a child’s introduction to the Rosary, and that the Passagalia might sum up in some way all the preceding 15 sonatas. This bore some fruit: clearly there are sections that could mirror the Crucifixion and Resurrection (bars 92-100 and 103-106) but it was not at all clear how the three sets of Mysteries (Five Joyful, Five Sorrowful and 5 Glorious) could be mirrored by sections of the Passagalia. It then occurred to me, inspired by the fact that the music seems to go over ‘old ground’ in the final bars, that the angel may well be leading the child through some sort of musical maze. This was the start of a series of much more compelling discoveries. To my astonishment, I found that the music fitted into a square structure rather like a maze and that this in turn threw up all sorts of beautiful and fascinating symmetries:

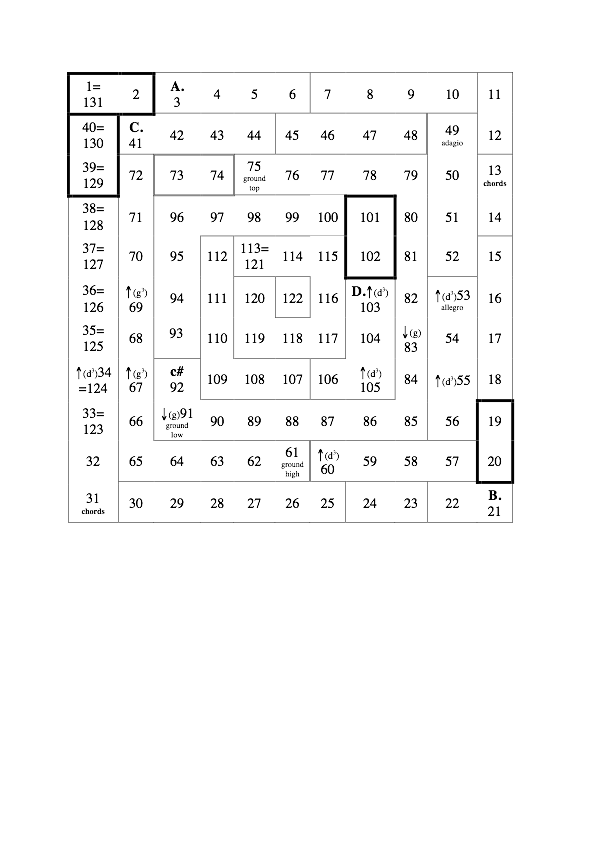

Biber’s Passagalia in diagrammatic form:

The Rosary and The Spiritual Exercises

Clearly this could be a maze, but what is its significance? Eventually, a breakthrough came when I was reminded of the derivation of the word ‘rosary’: This 11 x 11 square with its spiral could be drawn as a circular diagram, representing the petals of a rose, a symbol of the Virgin Mary herself. Moreover, if this work is such a strong Jesuit symbol, then perhaps it could also reflect that cornerstone of the Jesuits’ faith, The Spiritual Exercises of St Ignatius, an instruction manual for devotion published widely during the seventeenth century. The book is divided into four (unequal) ‘weeks’ of devotion, which concentrate in turn on the contemplation of sin, the life of Jesus, the Passion of Jesus and the Resurrection. Here, I believe, is the key to the Passagalia: the four ‘weeks’ are clearly reflected in the music – the first three each starting at a corner.

1-18A. (Week 1) Contemplation of Sin [18 bars]

19-38B. (Week 2) Life of Jesus [20 bars]

39-100C. (Week 3) The Passion [62 bars, divided 34 + 28 by the appearance of the ground bass up an octave]

101-122D. (Week 4) The Resurrection [22 bars]

123-132final section echoing bar 33 onwards [10 bars]

As one would expect from the great number of details given in the third ‘week’ of the Spiritual Exercises, by far the longest section is the meditation on the Passion. That it ends at bar 100 is surely not a coincidence, the number 100 traditionally representing perfection.

All that remains is to try to fit the various meditations in the Spiritual

Exercises into the various sections: a much more difficult task! In the first week there are five ‘days’ of different meditations: there do seem to be five obvious musical ideas: bars 3-6, 7-10, 11-12, 13-14, 15-18 and it may be that each of these could be a different meditation on the idea of sin.

In the following ‘week’, bars 19-38, representing the life of Jesus, there are more ideas and at present I am at a loss to assign different musical ideas to the meditations. Interestingly though, bars 23-24 have a close musical parallel in bars 59-60, and they are close to each other on the spiral. This could, I suppose, represent a reference to the Passion in an earlier event in the life of Jesus.

In the third section, the ‘weeping’ adagio section could be interpreted as droops of blood-like sweat in the ‘Agony in the Garden’, the remarkably violent passage from 67 to 72 may represent scourging, the passage from 61, where the bass part rises up the octave could symbolise crowning with thorns, and the long procession of 73-92, where the ground bass reaches the top of the texture, could represent carrying the cross. As already suggested, 93-100 must represent Crucifixion and death and 103-106 the Resurrection. And whenever I play the section from 113 to 122 the sensation is almost of flying: what else must this be than a violinist’s picture of the Ascension, appropriately reaching the centre of the spiral.

At this moment, why the reappearance of music from the ‘life of Christ’? I can only deduce that having completed the four ‘weeks’ of meditation, one can truly walk in the footsteps of Christ – I only hope this interpretation is not too close to blasphemy!

Further Numbers and Symbols

1. As already noted, the number 66 is a multiple of 33 the years of Christ’s life. Perhaps it is no coincidence that in bar 123, the final quotation from the life of Christ starts at bar 33 in the spiral, suggesting that a Christian follows on from Christ’s own life.

2. 66 is also a multiple of 22, which represents ‘X’ in the Latin natural-order alphabet (a=1, b=2 etc. with i and j, and u and v sharing a number), a sign for the Crucifixion.

3. Significant too is the range of the violin used in each section. It is not until the second section that top D is reached, making a range of 2 octaves (d1 – d3). In the third section the range opens up considerably to 3 octaves (g - g3) and this I presume represents the perfection of God. Diagrams with monochords divided into 2 octaves and 3 octaves (22 notes!) occur in the writings of 17th century philosopher, Robert Fludd, showing the chain of being between earth and God, and a diagram of the Ptolemaic universe has 22 steps between God and Earth.

4. Is the cross formed by extremes of pitch, marked by and in the diagram (bars 103, 53, 83, 105 and 55) an accident?

5. The only C# in the piece, with its accompanying chromatic treatment of the ground must also be a symbol for the crucifixion.

6. The very shape of the spiral 112 (11 x 11) may be significant. The number 121 is the total of 1 + 3 + 9 + 27 + 81, numbers of the Trinity.

11 x 11 x 11 or 113 is 1331 and even this number may be hinted at: chordal passages start at bars 13 and 31.

7. Using the Latin natural order alphabet again, the four notes of the ground bass, G, F, Eb, D = 7 + 6 + 5 + 4 = 22

Conclusion

In 1676, Heinrich Biber wrote of his ‘faith in stringed instruments (fidem in fidibus)’. If my interpretation is correct, then this faith is clearly expressed in just one string instrument in a piece that is truly both dramatic and spiritual.

Bibliography

J Clements, Penetrating the Mysteries

(at www.bluntinstrument.org.uk/biber/penetrating.htm)

J Godwin, Robert Fludd (Boulder 1979)

D Humphreys, The Esoteric Structure of Bach’s Clavierübung III

(University College Cardiff Press 1983)

St Ignatius of Loyola, Personal Writings (Penguin 1996)

R Tatlow, Bach and the riddle of the number alphabet

(Cambridge University Press 1991)

Edition

Download a ‘modernised urtext’ edited by John Tufvesson at IMSLP.

However, the following corrections are needed:

bar 18 (trill missing on F#)

bar 42 (natural sign missing from final E)

bar 72 (3rd note in top part should be C)

© Tony Urbainczyk

28th April 2013

Friday, 6 September 2013